Federated Learning

In the past few years, machine learning has led to major breakthroughs in various areas, such as natural language processing, computer vision and speech recognition [1] . Much of this success has been based on collecting huge amounts of data. For example, one of Facebook’s latest Detectron models for object detection was trained on 3.5 billion images from Instagram.

For some applications of machine learning, this need of collecting data can be incredibly privacy-invasive. One such example application is predicting the next word that a person is going to use by considering the previous words. This is typically done using machine learning nowadays, e.g. with recurrent neural networks and LSTMs [2] . Although it is possible to train such a model using a text corpus from Wikipedia, the language found there differs from the one typically used by people in daily life.

One potential use case for such a model is to improve the results of speech recognition, another one to predict the next word that is typed on a mobile phone to help people type more quickly. In both cases, it would be beneficial to directly train on that data instead of using text from Wikipedia. This would allow training a model on the same data distribution that is also used for making predictions. However, directly collecting this data is a terrible idea because it is extremely private. Users do not want to send everything they type to a server.

Sending only randomized versions of the original data to the server, based on the ideas of Differential Privacy, is one potential solution to this problem. The second solution is Federated Learning, a new approach to machine learning where the training data does not leave the users’ computer at all. Instead of sharing their data, users compute weight updates themselves using their locally available data. It is a way of training a model without directly inspecting users’ data on a server. This blog post gives a high-level introduction to Federated Learning and the challenges that arise in this problem setting.

Federated Optimization

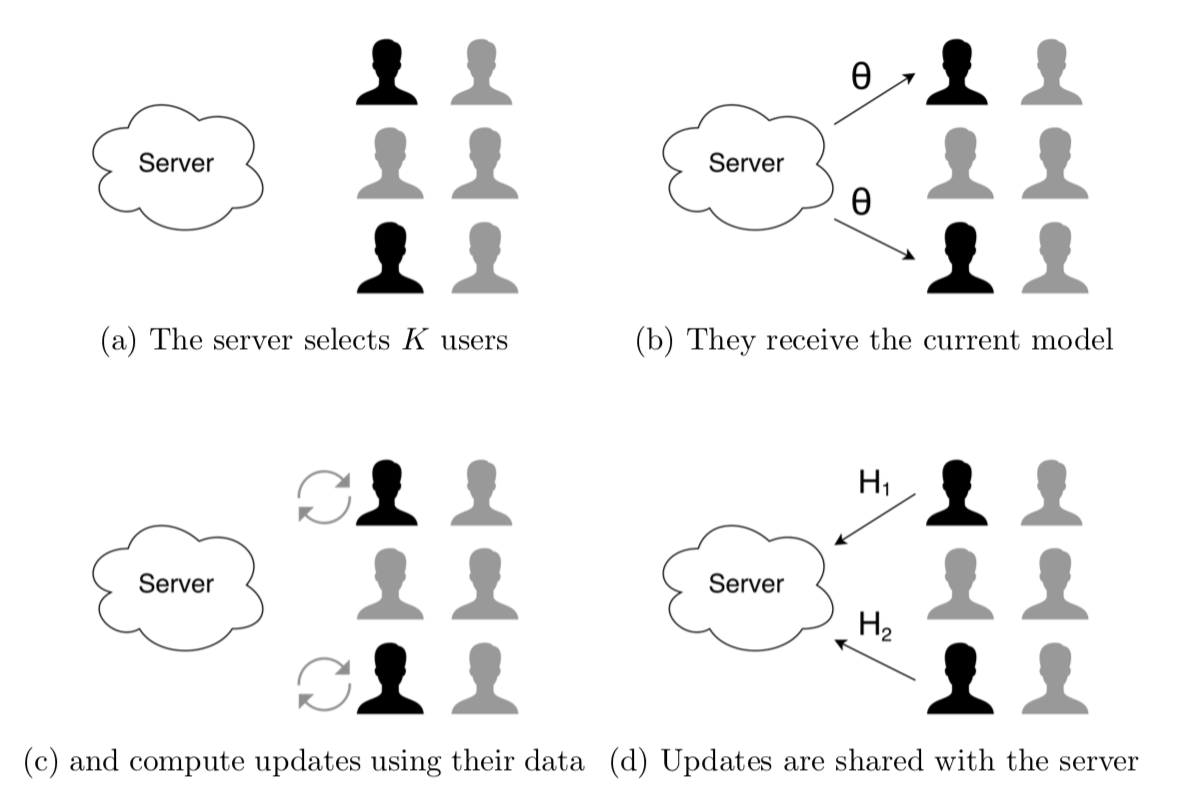

Federated Learning is a collaborative form of machine learning where the training process is distributed among many users. A server has the role of coordinating everything but most of the work is not performed by a central entity anymore but by a federation of users.

Before the start of the actual training process, the server initializes the model. Theoretically, this can be done arbitrarily, by using any of the common neural network initialization strategies or the equivalent for other model types. In practice, it is a good idea to use publicly available data to pretrain the model. For the example given above, this could be done by using text from Wikipedia. Although this does not produce the best possible model, it is a good starting point and can reduce the time until the Federated Learning process converges.

After the model is initialized, a certain number of users are randomly selected to improve the model. Each sampled user receives the current model from the server and uses their locally available data to compute a model update \(H_i\). All these updates are sent back to the server where they are averaged, weighted by the number of training examples that the respective clients used. The server then applies this update to the model, typically by using some form of gradient descent.

All of this is called a communication round. This process is then performed many times until the parameters of the model stabilize. Ideally, this happens after as few communication rounds as possible. To this end, it helps if the updates given by the users have a high quality. For models that we train based on gradient descent, one useful approach is to take several steps of stochastic gradient descent locally on the user’s computer before sending the weight update back to the server [3] .

The hyperparameter that determines how many users are sampled in each communication round also influences how many rounds are required until convergence is reached. However, at some point the average that is computed stabilizes and utilizing more users per round does not help to significantly reduce the number of communication rounds further. Thus, it makes sense to only query a smaller number of users in each iteration.

Applications

In principle, this idea can be applied to any model for which some notion of updates can be defined. This naturally includes everything based on gradient descent, which most of the popular models nowadays are. Linear regression, logistic regression, neural networks and linear support vector machines can all be used for Federated Learning by letting users compute gradients.

There are other models that are not based on gradients but where it is possible to define updates. For k-means clustering, updates could correspond to moving the cluster centers. If users compute the position of the new centers based on their local data, the weighted average across all these results gives us the true new position. Similar averages can be used with the power iteration method to implement a distributed version of PCA. For some other models like decision trees, it can be much harder to think of a federated version that allows for continuous updates.

In terms of data, Federated Learning is especially useful in situations where users generate and label data themselves implicitly. This is the case for the application of trying to predict the next word. While users type on their keyboards, the model tries to predict the next word. As soon as the user typed the next word, a new data point is created and the true label (the last word) is determined. The model can then automatically update itself without having to store the data permanently. In such a situation, Federated Learning is extremely powerful because models can be trained with a huge amount of data that is not stored and not directly shared with a server at all. We can thus make use of a lot of data that we could otherwise not have used without violating the users’ privacy.

Unique Characteristics

While Federated Learning might sound similar to distributed machine learning on a technical level, there are some major differences to applications in data centers where the training data is distributed among many machines [4] .

- Huge number of clients: Since machine learning generally requires a lot of data, the applications that use it have to have many users. Every one of these users could theoretically participate in Federated Learning, making it far more distributed than anything in a data center

- Non-identical distributions: In a data center setting, it is possible to ensure that every machine has a representative set of data so that all updates look very similar. In Federated Learning, this cannot be guaranteed. We have to expect that users generate data from completely different distributions, i.e. we cannot make iid assumptions. While similar users might have similar local training data, two randomly picked users could produce very different weight updates

- Unbalanced number of samples: Along the same lines, we cannot expect most users to have the same number of local training examples. There could be users with only a handful of data points, while others might have thousands

- Slow and unstable communication: In a data center, it is expected that nodes can communicate comparatively quickly with each other and that it is ensured that messages do not get lost. In Federated Learning, these assumptions cannot be made. Uploads are typically going to be much slower than downloads and, especially if the connection is from a cell phone, it might be extremely slow. Some clients might also currently not be connected to the internet and will not respond at all

These properties motivate why Federated Learning requires its own specialized algorithms.

Compression

Neural networks commonly have millions of parameters nowadays. Sending updates for so many values to a server leads to huge communication costs with a growing number of users and iterations. Thus, a naive approach to sharing weight updates is not feasible for larger models. Since uploads are typically much slower than downloads, it is acceptable that users have to download the current model, while compression methods should be applied to the uploaded data.

Of course, lossless compression techniques can be used and it might make sense to only send updates once a good network connection is possible. Additionally, specialized compression techniques for Federated Learning can be applied [4] . Since only the average update is required to compute the next model, these compression methods try to encode updates with fewer bits while keeping the average stable. It is acceptable that individual updates are compressed in a lossy manner, as long as the overall average does not change too much.

On a high level, compression algorithms for Federated Learning can be put into two classes:

- Sketched updates: Clients compute a normal weight update and perform a compression afterwards. The compressed update is often an unbiased estimator of the true update, meaning they are the same on average. One of the more sophisticated such techniques is Probabilistic Quantization, which I described in more detail in another blog post

- Structured updates: During the optimization process, the update is restricted to be of a form that allows for an efficient compression. For example, the updates might be forced to be sparse or low-rank. The optimization then finds the best possible update of this form

There are no strong guarantees about which method works the best. It heavily depends on the problem and the distributions of the updates. Like in many parts of machine learning, different methods just have to be tested and are compared empirically.

Privacy

On a first look, Federated Learning seems like a method that it is very privacy-friendly. However, one could think about an attacker that analyzes the weights to make conclusions about the data of users [5] . If the behavior of the coordinating server is also adversarial, the model could be a neural network with so much capacity that it overfits badly. Since neural networks are universal function approximators, this model might just learn to approximate the function that directly acts as a look-up table to the data used for training. In this case, the user’s data would not be private because it is still represented more or less clearly in the model.

While this might sound unlikely if not done on purpose, there have been experiments that show it is possible to reconstruct some data points. In one case, researchers were able to reconstruct images of faces that were used to train a face recognition model [6] .

Differential Privacy, which I wrote about in another post, is one solution to this problem. By formalizing what privacy means, we can analyze how well the learning algorithm respects privacy. To employ this technique to Federated Learning, the notion of privacy is adapted to a user level: It should be very hard to tell whether a user contributed to the training of the model. This is done using a stochastic framework. By adding noise to update data shared by the user, the reports of individuals become much harder to analyze, while the noise can be estimated well for the aggregated data.

Concretely, this involves several changes to the previous Federated Learning algorithm [6] :

- Users are randomly sampled with some probability instead of always sampling a fixed number of users. This is to ensure that users can still be sampled independently of each other. More sophisticated techniques than simple sampling should not be used because they might add a bias for certain users, which makes it more difficult to ensure their privacy

- The updates that users send to the server need to have a bounded L2 norm. This limits how much individuals can influence the final weights. The motivation is that it should be prevented that individuals can be identified because they are the only ones who would propose large updates. In the case of neural networks, bounding the norm corresponds to gradient clipping

- Noise is added to the final update for the model, similar to most Differential Privacy algorithms

In experiments, it has been shown that the same accuracy as before can be achieved with these changes [6] . However, the computational cost to get there is much higher. In a real implementation, this could correspond to a slower convergence rate.

Encryption

Encryption for Federated Learning is a topic that is close to the privacy aspect previously discussed. By using cryptography techniques, it is possible to ensure that the updates of individuals can only be read when enough users submitted updates [7] . This makes man-in-the-middle attacks much harder: An attacker cannot make conclusions about the training data based on the intercepted network activity of an individual user. To be able to do that, they would need to intercept the messages of many users.

Personalization

A potential extension of Federated Learning could be customization. While users help to train a central model, they also locally personalize it using their own data. A simple implementation of this is a two-phase training process. In the first step, a central model is collaboratively trained by all users. After that, users locally adapt the model to their own preferences.

This approach has an obvious drawback: Once users start personalizing the model, they cannot help to train the central one anymore. That might be bad because there could be situations where the model becomes outdated. A second approach is to personalize the input that the model receives. Additionally to the actual input, the model also receives a personalized vector which encodes the preferences of the respective user.

Once the model itself was trained to a sufficient quality, users start optimizing the personalized vector as well. The centralized model is still improved periodically. Over time, the centralized model keeps improving and adapting to changes, while users can also keep improving their personalization settings.

Summary

Current machine learning approaches require the availability of large datasets. These are usually created by collecting huge amounts of data from users. Federated Learning is a more flexible technique that allows training a model without directly seeing the data. Although the learning algorithm is used in a distributed way, Federated Learning is very different to the way machine learning is used in data centers. Many guarantees about distributions cannot be made and communication is often slow and unstable.

To be able to perform Federated Learning efficiently, optimization algorithms can be adapted and various compression schemes can be used. The privacy aspect can be tackled using Differential Privacy and encryption. Since the system in general is quite flexible, it can be adapted to allow for locally personalized models. Although there have been several papers about Federated Learning, it is still quite new and not many uses of it were reported by the industry yet.

References

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. and Hinton, G., 2015. Deep learning. nature, 521(7553), p.436.

- Sundermeyer, M., Schlüter, R. and Ney, H., 2012. LSTM neural networks for language modeling. In Thirteenth Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association.

- McMahan, H.B., Moore, E., Ramage, D. and Hampson, S., 2016. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.05629.

- Konečný, J., McMahan, H.B., Yu, F.X., Richtárik, P., Suresh, A.T. and Bacon, D., 2016. Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.05492.

- McMahan, H.B., Ramage, D., Talwar, K. and Zhang, L., 2017. Learning differentially private language models without losing accuracy. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.06963.

- Fredrikson, M., Jha, S. and Ristenpart, T., 2015, October. Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 1322-1333). ACM.

- Bonawitz, K., Ivanov, V., Kreuter, B., Marcedone, A., McMahan, H.B., Patel, S., Ramage, D., Segal, A. and Seth, K., 2017, October. Practical Secure Aggregation for Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 1175-1191). ACM.