Quines

Quines are programs that when executed produce a copy of their own source code. Writing quines is a neat little programming exercise and turns out to be more difficult than one would think at first.

Disclaimer: If you never attempted to write your own quine, you should definitely stop reading this article. Come back when you managed to get your own quine working or at least spent a good amount of time in trying to do so. Quines are interesting in that the solution looks fairly trivial even though it can be very hard to come up with it on your own.

Originally, quines were proposed by Douglas Hofstadter in Gödel, Escher, Bach [1] . Ken Thompson’s Turing Award lecture Reflecting on Trusting Trust [2] also begins with a description of them:

”In college, before video games, we would amuse ourselves by posing programming exercises. One of the favorites was to write the shortest self-reproducing program. Since this is an exercise divorced from reality, the usual vehicle was FORTRAN. Actually, FORTRAN was the language of choice for the same reason that three-legged races are popular.“ – Ken Thompson

We will get back to that speech later on.

Rules

The rules are fairly straightforward. The program, when compiled and executed, needs to output its own source code. It must do so without using IO to read its own source code file. In other words, a shell program such as this one would not be allowed:

cat script.sh

For the sake of keeping the challenge interesting, an empty program is also disallowed. Technically, it outputs its own source code, the empty string, but that would be a boring solution.

A first attempt

How hard could trying to output the source code be? Can we not simply print it?

print('print("x")')

It quickly becomes evident that this approach will not work.

We are missing the outer print and adding more print statements to the string will not change that.

Ruby preliminaries

In the remaining blog post, I am going to use Ruby since its syntax makes it a little bit more elegant to write a quine. Still, the resulting code is fairly similar to Python.

Ruby has heredocs, which allow us to store strings without needing to worry about escaping quotes. It turns out that this is extremely useful for what we want to do.

s = <<-STR

Everything until STR on its own line is part of the string.

We do not need to escape " or '

STR

The puts function is similar to print in Python.

Adding several arguments means every argument is printed on its own line:

puts(1, 2, 3)

The result is equivalent to print(1); print(2); print(3) in Python:

1

2

3

Data and code

The solution to writing a quine is to divide the program into data and code parts.

In the data section, we store the code section as a string s.

The subsequent code section is responsible for reproducing the entire program.

It does this by printing s twice:

- The first time, we print

sbut surround it with strings to print code for storing it in a variables. This reproduces the data section - The second time, we just print

s. Sincescontains the code section itself, this perfectly reproduces it

Since we printed both the data and the code sections, we managed to reproduce the entire program. In Ruby, this might look something like this:

s = <<-STR

puts("s = <<-STR", s, "STR", s)

STR

puts("s = <<-STR", s, "STR", s)

The first three arguments to puts print the data section, while the remaining one takes care of the code section.

We can confirm that it works by running the program and piping its output back to Ruby, to run it again:

$ ruby quine.rb | ruby

As expected, this outputs our program again, as would piping it to Ruby another time. Success!

The original goal was to write the shortest possible quine. But since this just reduces down to code golfing, it is not part of this blog post.

Digression: A Python equivalent

The equivalent in Python is not too different:

s = 'print("s = ", repr(s)); print(s)'

print("s =", repr(s)); print(s)

repr returns the representation of a string.

For example, repr("a") would return '"a"'.

This also allows us to circumvent the problem of escaping strings.

However, it is a bit less elegant since we need to make the assumption that repr is going to surround the input with ', rather than ".

Again, we can confirm that this works:

$ python3 quine.py | python3

Of course, handling the escaping logic ourselves, or adding new lines to make the program more readable, would also be possible. It would just increase the complexity of the script a little bit.

Programs that produce self-producing programs

Storing the actual code twice, once as a string in the data section and then as code, is not too elegant.

A cooler idea is to write a program that outputs a quine.

To do so, we create a new file quine_producer.rb.

In the data section, we use IO to read the second line of its own file, which corresponds to the code section:

s = IO.readlines("quine_producer.rb")[1]

puts('s = <<-STR', s, 'STR', s)

This program uses IO and does not output its own program, so it cannot be a quine.

However, its output is a program, equal to quine.rb, which does not use IO and produces its own source code:

$ ruby quine_producer.rb | ruby | ruby

At this point, we could actually add more code to the program, while still keeping it a quine. By reading everything after the first line, we can add anything we want to.

We need to go deeper

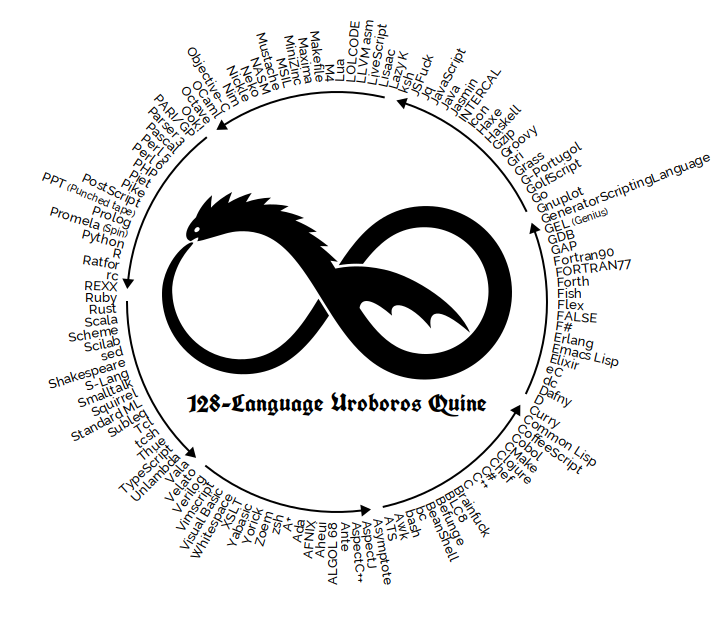

The quine relay takes this idea to the extreme. Instead of just printing its own source code, the program is a Ruby script that outputs a Rust program which outputs a Scala program and so on, until at some point the original Ruby code is reproduced. Again, if you have not attempted to implement something like this, I would recommend taking some time to do so before reading on.

|

Conceptually, the quine relay is actually not a huge step above of what we already implemented. Let’s try to create a minimal version based on what we already have. We will write a Python script that outputs a Ruby program which should reproduce our original program. To get by without escaping quotes, we will start from the Python version. This allows us to fully use Ruby’s heredoc.

The Ruby program here can actually be rather simple.

It just needs to print its input, which is the original Python script.

Adding more languages to this chain (or rather circle) would be trivial, we just need to wrap a lot of print statements.

The Python script does most of the work:

s = 'print("puts <<-STR"); print("s =", repr(s)); print(s); print("STR")'

print("puts <<-STR"); print("s =", repr(s)); print(s); print("STR")

The code is not getting more readable at this point, but we really just wrapped the code section with print statements for Ruby’s puts and heredoc.

Running the script yields a Ruby program which outputs our original Python script.

We can keep going in that circle:

$ python3 quine-relay.py | ruby | python3 | ruby | python3

The remaining part of scaling this up to more languages is handling the escaping of quotes.

The above code only works because the heredoc waits for a line that solely contains STR.

Adding more languages without heredocs would require logic for escaping.

Reflections on Trusting Trust

Ken Thompson’s Turing Award speech [2] begins by introducing quines. It then goes on to show another interesting case of self-reproducing programs, in the area of compilers.

Many languages have compilers that were written in the language itself. C used to be a popular example of this. To compile C, people used to use a compiler written in C. Java, Go, Rust and Haskell are some languages where this is still true to this day. I still find it amazing that this works, even though I first learned about it years ago.

To be able to pull this off, we need to bootstrap. The very first compiler we use has to be written in a different language. Once it is functional, the compiler can be reimplemented in the language itself and is built using the original compiler. From then on, the new compiler can be used.

Now, let’s suppose someone wanted to add malicious code to the compiler.

Whenever it is used to compile login, it should add a backdoor.

Such code in the compiler would quickly be found and removed.

However, an attacker could also implement another check to see if the compiler itself is getting compiled.

If so, the malicious code with both checks is added.

Otherwise, if neither the compiler nor login are getting compiled, nothing is added.

If the attacker is able to replace the system compiler, they could then remove anything malicious from the compiler source code.

However, whenever someone is compiling something new, the backdoors could get added.

Thompson calls this a learning program. We teach it once to add the malicious code. After recompiling it, the program knows how to add the code and keeps on reproducing it.

It would be impossible to get rid of the malicious code since it is reproduced every time the compiler gets recompiled. A post on Quora describes this exact attack. The only way not to have the backdoor would be to use a different compiler. The fact that this is possible leads to further questions: What tools and systems can we really trust? Since we always built on top of something existing, it is impossible to be fully certain that no malicious, self-reproducing code is added anywhere.